Jazzpunk is a difficult game to categorize. You can break it down into identifiable mechanics: First Person, Adventure, Narrative, Comedy, and so on. Yet the entire work as a composition can’t easily be thrust into a concrete genre. Essentially, it could be considered an adventure game in the same vein as Gone Home or Dear Esther; however there’s far more player interaction then would be expected from these types of games. While most games in the Adventure Genre lead you into experiencing a world, clue by clue from puzzle to puzzle, Jazzpunk instead places you in a position to become fully involved in the setting to often ridiculous and comical ends.

Good comedy in video games is challenging to write. Part of it is due to the nature of game development, specifically in the bottom-up process of design, where a designer makes a collection of mechanics fun and playable, then attempts to write a story that tries to explain their purpose. That’s not a bad design principle; many games well known for their stories such as Bioshock are built with this process. The problem lies with the key principle of what makes good comedy: timing.

When gameplay is handed over to any unknown player, you can’t predict what their process of exploration will be without limiting or forcibly taking away their control. This is why comedy in games is often restricted to linear segments, readable notes, or cut scenes. You Don’t Know Jack forces the player to watch a blank screen while jokes are told to them. No One Lives Forever confines most of its humorous writing into collectable notes or between enemy characters that are casually in conversation before being alerted by the player. Borderlands two’s comedy is almost entirely based in Handsome Jack’s audio logs. While this sort of comedy games is still clever and hilarious, designers are forced to place these moments around players rather than have them directly involved with the joke.

It’s interesting, then, that often times far more serious games can have player-driven humor through emergent means. Far Cry 2’s systems of weapon degradation and frequent enemy checkpoints can lead players into hilariously tense firefights that end with your character looking completely incompetent. AI bugs, randomized dialogue, and player’s environment interactions can create some bizarre and hilarious moments in Bethesda games like Fallout 3 and Skyrim. In fact, pretty much any game with simulated physics can create an assortment of slapstick-style humor. The problem here is that these games aren’t meant to be comedies, and often designers and coders try to stop these moments from happening as they break away from the immersion that the world is supposed to bring.

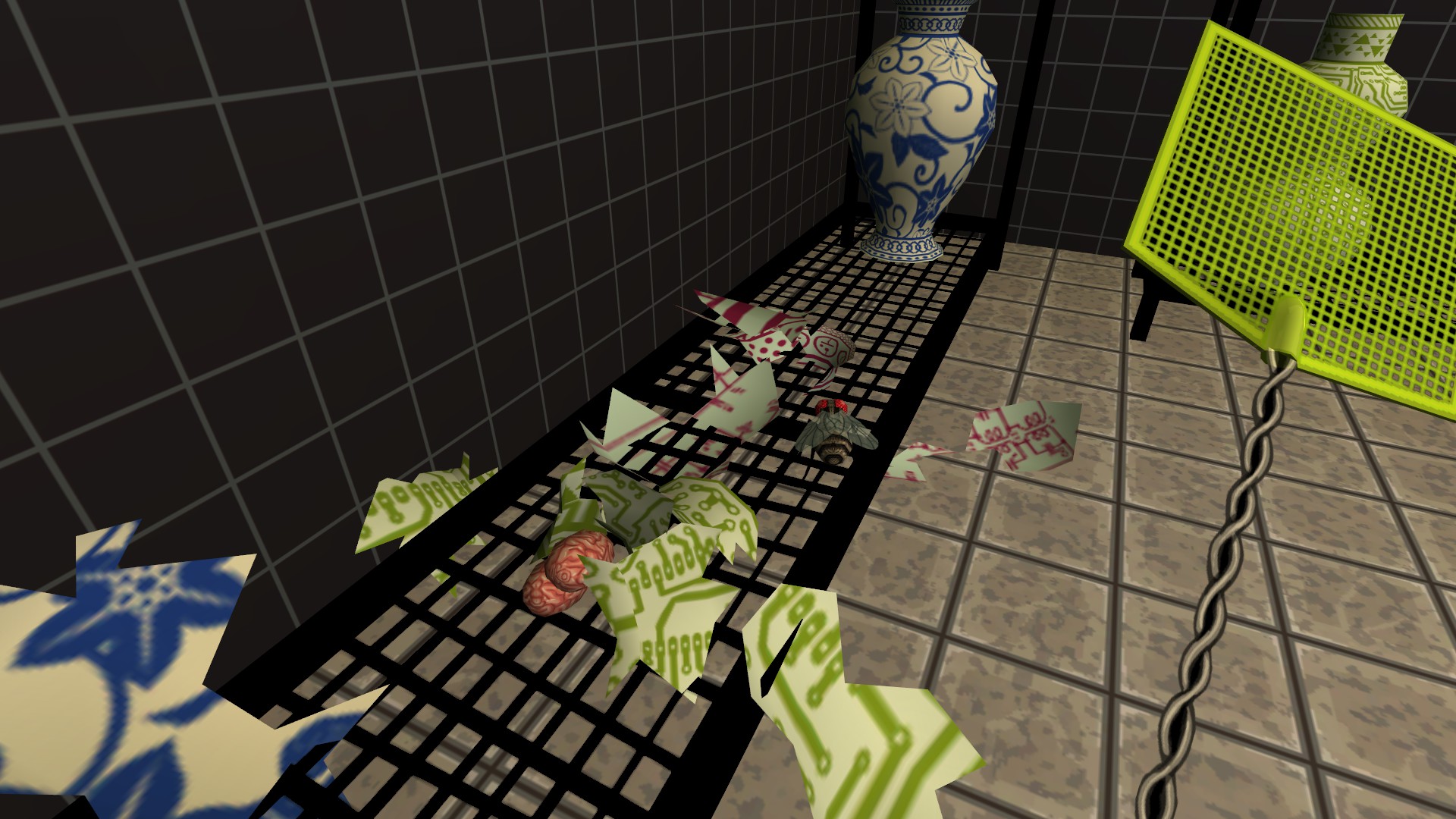

Jazzpunk, through means of its own systems and narrative, attempts to take on both of these concepts and work it into a fully functional piece. While the game itself is considerably short in length, there is a surprising amount of depth worked into every player interaction within the world presented. On the surface layer lies what you would expect: A single button press will set something in motion, be it a one-off gag or a funny line. Yet as the player progresses the more they find themselves fully involved in the punch line. At one point a character asks you to kill flies in in her shop. As you enter, you’re immediately given a fly swatter and Flight of the Bumblebees begins to play. However, as you make your first swing, you find the shop is completely fully of china and by the time you’ve completed your task half of the store is left in ruin.

It would seem that the process of this game’s design must have come from a monumental QA session. With the limited inventory you’re given, almost every potential interaction is accounted for and rewarded with some form of gag. It’s surprisingly similar to the adventure games made by Humongous Entertainment in the late 90s. While you were given an objective and a set of tools to accomplish your task, players could click on nearly any art asset in the world for some sort of reaction. In many ways, Jazzpunk operates in the same way. If the player never strays from the critical path, they could easily miss most of what this game has to offer. It’s clear the developers were aware of this, as the game is designed in such a way that you easily find yourself wandering off. While clear directions are given for each objective, you’re not often told what direction to take or what to do, relying instead on your own interaction to find the solution.

In some ways, Jazzpunk feels like a critical response to Galactic Café’s “The Stanley Parable”, released late last year. The Stanley Parable made fun of the idea of pre-established narrative, and that even when breaking it within the game’s mechanics you’re still a part of a script which you could never escape. Jazzpunk takes the same concept and shows that even though there is no game allows for a player to be truly free, you can give the illusion of an open world by simply covering every hole and fill every potential interaction the player could have with some sort of unique reaction. It’s a detail intensive process, yet the outcome leads to an incredibly immersive joke simulation.

Be First to Comment